If you purchase an independently reviewed item through our site, we earn an affiliate commission. Read our affiliate disclosure.

Mason bees are natural pollinators in many ecosystems. Learning about the mason bee life cycle is important so that you know how to benefit as much as possible from these bees. They are the native bees of North America, including the USA. Various developments have led to an increasing interest in mason bees, particularly the decline in honeybee populations across the USA and the world.

Mason bees are an important pollinator, and are useful in filling pollination gaps that might arise from time to time as we look for solutions to the challenges facing honeybee populations. There are more than 300 species of bees in the genus Osmia that can be referred to as mason bees. A distinction in popular use is, however, emerging with the name ‘Mason Bee’ being used to refer to the Osmia bees that use mud, and other soil-based materials to make some or all of their nests. Those that use plant-based materials such as flower petals and leaves are now generally referred to as leafcutter bees.

In this article, we generally look at the Osmia species that use mud and soil-based materials in their nests and emerge in early spring season. Even then, the life cycle of these mason bees do not have any wide variance from that of leafcutter bees. Only a few differences exist between the life cycles of mason bees and leafcutter bees such as the choice of nest materials, the preferred diameter of holes for nesting, and the season of emergence and major pollination activity.

The Mason Bee Life Cycle

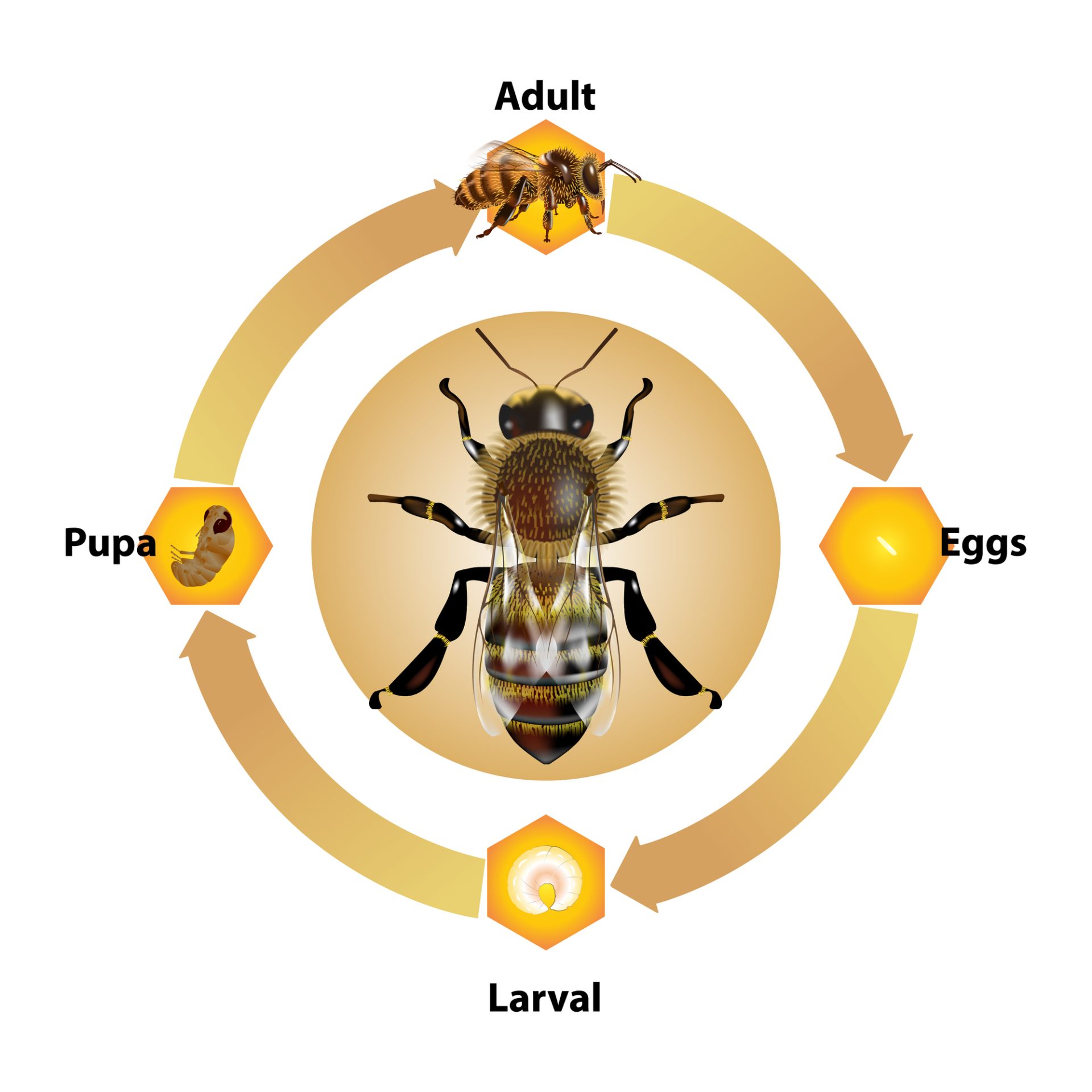

The mason bee life cycle follows the classic stages and steps of insect life with complete metamorphosis:

- Adult mason bees lay eggs that hatch to release larvae;

- Next, the larvae turn into pupae with cocoons around individual pupa;

- Lastly, the pupae emerge as adults from the cocoons in which they pupate.

Mason bees do not shed their exoskeletons (do not undergo ecdysis) once they emerge from their cocoon having reached the adult stage.

A mason bee has three distinct body parts: head, thorax and abdomen. On the head, there are two large compound eyes, three small ocelli, a mouth and antennae. The thorax holds four wings and six legs. On Osmia females, there is a scopa underneath the abdomen for collecting females. The scopa is absent in male mason bees.

Mason Bee Eggs

Mason bee eggs are laid by female adult mason bees. They are usually fertilized eggs. Most female mason bees lay eggs in an arrangement that sees the male mason bees emerging first from the nest tubes. It means that the adult females lay the eggs for producing female mason bees first, towards the rear or closed end of nesting tubes. They lay the eggs for producing males as the last few eggs towards the end of the nesting tube that is open, or the entrance. This arrangement of eggs allows male mason bees to emerge first from their cocoons and be ready to mate with female mason bees.

Each mason bee egg is laid in a pollen bed. Adult female mason bees collect the pollen from various sources and deposit it into a nest cell. They lay the egg on the pollen and then seal the nest. Some mason bees may line the nest with nesting material such as mud. After some time, the egg hatches and releases a larva in the pollen bed.

Mason Bee Larvae

Eggs of mason bees release larvae when they hatch. Each larva has access to its nest cell and the pollen in the nest cell. It immediately starts eating the pollen in its nest cell and increases in its size. The larva continues feeding until it has consumed all the pollen in its nest cell. Its feeding takes a few weeks to exhaust the pollen and nectar provision mass in each nest cell. The larva then spins a cocoon around itself and enters the pupal stage.

Mason Bee Pupae

Mason bee pupae are the form in which mason bees get through winter. The pupae develop slowly and turn into adults. In some species of mason bees, especially those that emerge in early spring, the pupae turn into adults in the fall but remain in hibernation in the insulating cocoon. The pupae of most mason bees that emerge in summer turn into adults during winter. At the end of their developments, they emerge from the cocoons as adult mason bees.

There are many mason bee species in the USA in regions that see temperatures drop to below 00C (320F) for significant periods of time. They have adaptation to the cold and even seem to require chilling for proper development and maturation.

A few mason bee species take two years to develop from egg to adult, with a full year spent as larva. Most other mason bees develop from egg to adult stage in one year.

Adult Mason Bees

When the development of the mason bee pupae is complete, adults emerge from their respective cocoons. This happens in early spring season. Often, males emerge first and get used to their environment while firming up their wings. They drink nectar from early spring flowers and wait 3-5 days for the female mason bees to emerge. When the females emerge from their cocoons and nesting tubes, the males mate with them.

Mating in mason bees has a marked difference from that of honeybees. In mason bees, the male does not die after mating with a female mason bee. The male can mate with many females until his death. One female mason bee can also mate with several males.

Some male mason bees have been observed extracting females from their cocoons and then mating with them. Male mason bees die a week or two after they have mated with females. This leaves the female bees as the larger population of mason bees in the ecosystem. After mating, female mason bees decide on where they will make their nests and start collecting materials for nest-making.

Life Cycle Activities of Female Mason Bees

The adult female mason bee is the active one in nest-making and, therefore, pollination. It inadvertently pollinates flowers of plants during its activities collecting pollen for its nest cells. Female mason bees additionally engage in other activities of interest to farmers, agriculturalists, researchers and humans at large. This is because the effects of mason bee activities impact entire ecosystems.

Nest Site Selection

Bees and insects are sometimes described based on their preference to work in teams or not. Mason bees are solitary. They do not cooperate on any life activities and have no known method of communicating. They can thus not signal each other even when there is danger such as the presence of predators. There is documentation, however, of the use of pheromones to inform succeeding generations about the best nesting sites for mason bees. This sees mason bees of the current generation preferring to nest in the same spaces where previous generations of mason bees nested.

All female mason bees are fertile. Each female makes her own nest independent of neighboring mason bee females and their nests. There is no worker bee class in mason bees and other Osmia bees.

Deciding where to nest is a one-time event for female mason bees. Once the female mason bee has decided where her nest will be, she will rarely go back to choosing a second site in her lifetime. Most mason bees make nests in the same nesting area that they emerged from. Typically, mason bees make nests in tubular cavities that are naturally occurring, narrow gaps and other hollows such as the abandoned nests of suitably sized wood-boring beetles and carpenter bees.

There is clear preference by mason bees to nesting in plant material such as wood, twigs and reeds. If a mason bee cannot find a suitable hollow in plant material for nesting, it makes use of any other available hollow that is of the suitable size. Mason bee nests have thus been found in all sorts of materials including snail shells, metal pipes and plastic tubes among others.

Mason Bee Nest Building Materials

Mason bees use different materials to build their nests and create optimum conditions for the survival of their eggs, larvae and pupae. Wet mud is the preferred material for mason bees, thus the ‘Mason’ name. Some types of bees in the Osmia genus use leaves and flower petals as the main material of their nests and only a little or no mud for the outer surfaces of their nest cells. These are subsequently popularly referred to as leafcutter bees.

Properties and Characteristics of Mason Bee Nest Materials

The mason bees that use mud as the primary nesting material may incorporate a little plant material that they chew to a fine pulp. The plant material improves the quality of mud that the mason bees have found, so that it has all the necessary properties including;

- The mud should be breathable so that there is exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the inside of the nest cells and environmental air. This is necessary because living things need oxygen for life. Similarly, the egg, larvae and pupae of mason bees need oxygen for respective viability and survival.

- The mud should be able to absorb some moisture and release it as necessary for the regulation of humidity inside the nest cell. This also means that the nesting mud material must be fast-drying. It cannot stay wet for too long and cool the egg, larva or pupa.

- The mud should be able to offer some resistance to erosion, even when wet. When dry, it should not flake or separate into pieces that fall off the walls of nest cells and leave the cell exposed to the elements.

- The mud should be hard enough to provide some impact resistance and protect the contents of the nest cell. Even then, it should not be too hard and present a lot of difficulty for the adult mason bee leaving the nest cell after it emerges from its cocoon.

How Mason Bees Build Their Nests

A mason bee nest is intriguing and comes from skillful building by the female bees of the species. They collect mud for making the nests using their mouths and fly it to the nesting area. In the nesting area, the mason bees wet the mud using their saliva and put it in place.

Mud placement in a mason bee’s nest starts at the innermost end of the nesting space that the mason bee has decided to use. The first mud that the bee places in the nesting space forms the rear end of the first cell. Building the cells in the nesting space continues in this manner, with progress seeing the building of subsequent nest cells in a series towards the entrance of the nesting space.

All mason bee nest cells are of the same size and ovoid shape. Each nest cell is roughly the same size as an adult mason bee. Mason bees shape the mud using their mouths. This is repeated during the entire time that the mason bee is building nesting cells. It builds each nesting cell to near completion and then stops for some time to collect pollen and nectar.

The female mason bee puts pollen and nectar into the cell until it has accumulated enough of this food to feed a larva. It then lays a single egg on top of the pollen bed that it has made. With enough pollen and nectar stored and an egg in the individual cell, the female mason bee now closes up the cell using mud. It then starts building the walls of the next cell in the series. The front end of one nest cell forms the rear end of the next nest cell in progression towards the entrance of the nesting space.

Mason Bee Nest Cell Alignment

The female bee stacks cells in a row or column depending on the vertical and horizontal orientations of the nesting space. Each nest cell has a longer side and a shorter one. Female mason bees make nest cells with the longer side aligned to the entrance of the nesting space. If the nesting space is level, with the entrance being to the side, the cells will be in rows and the longer side of the nesting cells will be the horizontal side. Where the entrance to the mason bee’s nesting space is at the top or bottom, the cells will be in a column with the longer side being the vertical side.

Naturally occurring nesting spaces of mason bees are not regular in shape. In an irregularly shaped space, the mason bee plugs the extra space with its preferred nest-making material if the space cannot take more than once nest cell. If the space can hold more than one nest cell, the mason bee will build more than once nest cell in a column or row, respectively.

Alignment of the nesting cell with the longer side denoting the entrance of the nesting space helps the emerging adults to leave their cells with ease. It also helps to prevent occurrence of instances where an adult mason bee is unable to leave its nesting cell or the nesting area.

How Many Nests Does a Mason Bee Make?

Nesting cell construction in the mason bee life cycle continues until the mason bee dies. If it fills the nesting space it first chose, the bee plugs the entrance of the nest and moves on to building another nest in another suitable space. In mason beekeeping, the mason bee starts work on a second nesting tube if it fills the first nesting tube. Female mason bees live for 4-6 weeks before they die. This is the same average lifespan for all bees, except the queen bees in honeybee colonies.

Pollen and Nectar Collection

In its life cycle, the mason bee collects pollen and nectar from plants. The purpose of doing this is to provide the best food for its larvae. Some of the nectar that the mason bee drinks during collection trips is used up in its body as food to produce energy. During pollen and nectar collection trips, mason bees contribute to the pollination of plant flowers.

Mason bees have ventral scopae that hold pollen which the bee then flies to its nesting site. Most ventral scopae are black in color except on a few Osmia species. Each female mason bee makes many trips for her to fill just a single nest cell with pollen and nectar. Once she has completed making an adequate pollen and nectar provision mass, she will back into the nesting cell and lay a single egg on the pollen bed. This is followed by the closing of the cell using some mud.

Pollination by mason bees is very effective. Mason bees are efficient pollinators because they use scopa on their abdomens. These scopae have many hairs around them. Pollen often falls from the scopae onto the stigma of flowers. Mason bees perform pollination in nearly all flower visits except in very few flower visits. They are valuable pollinators due to this anatomy and behavior. It has led to farmers engaging in mason beekeeping where they manage populations of one or more species of mason bees.

Due to their emergence in early spring, mason bees are the dominant pollinators for early spring flowers. Mason bees forage even in poor weather conditions, further increasing their effectiveness and efficiency as pollinators.

Mason Bee Predators

Mason bees are immune from Varroa and acarine mites. They, however, still do have various pests, diseases and parasites that harm them. Additionally, there are fungi that cause infection and death of mason bees in the larva or pupa stages of development. Lastly, there are a few species of birds that predate on mason bees in their larval, pupal or adult forms.

About Mason Beekeeping

Mason bees do not produce honey or wax. Keeping and managing populations of mason bees primarily aims at benefitting from the pollination activities of the mason bees. Mason beekeeping uses structures that mostly provide round holes and tubes for mason bee nesting. These structures have undergone years of research and development. They can be reusable or single-use. Reusable mason beekeeping structures lower your operation’s costs. Mason bees also readily accept to nest in structures and spaces that have previously held other mason bee nests. Some mason beekeeping structures are mason bee houses, reeds, nesting trays, paper tubes and paper tube liners.

You can transport and propagate mason bees when they are in their cocoon form during the pupal stage of development. To start a population of mason bees going, you place the cocoons into the new nesting place that you have selected and prepared for the mason bees. When the mason bees emerge from their cocoons, they have preference to set up a nest in the space in which they emerged if it is suitable for their nests.

Mason bees are not aggressive, but they can sting you and animals. Despite their docility, they turn defensive when squeezed, when wet, and any other time when they feel threatened. Handling adult mason bees with your bare hands is not safe if you are inexperienced. The mason bee sting is not painful; the stinger is small and the does not have barbs.

Management, transportation of mason bees, and mason beekeeping in general needs careful attention to safety, hygiene and ethical practices to prevent the spread of mason bee diseases, pests and parasites. Additionally, you should take into account the possibility of applying pressure on other native bees and pollinators before you introduce new mason bee populations into an ecosystem.

Conclusion

Pollination of plant flowers is important for food production and fertilization which gives seeds and other benefits to both the plants and humans. Agriculture requires pollination to happen in a reliable and efficient manner for best crop yields. Various challenges in plant pollination have caused farmers to turn to mason bees and even engage in mason beekeeping.

Mason bees are great at complementing honeybees in pollination. They can also fill the gaps left by declining populations of honeybees where needed. Mason bees are native to the USA and North American continent. Apply the lessons from your learning about the mason bee life cycle to profitable ends and in making environments better for mason bees.

BeeKeepClub Resources and Guides for Beekeepers

BeeKeepClub Resources and Guides for Beekeepers